Anthony Cudahy: ceaseless arranger

GRIMM is pleased to present an exhibition of new paintings by Anthony Cudahy, on view at the Amsterdam gallery from August 29 to October 18, 2025.

The empty hand reaches toward the hose or rope. A snaking thing. A line. Three men—hunched or lying; touching, all of them—pass it to a standing fourth. Or take it from him. Does his hand reach, or would to impose any narrative, any intention, be projection? The right wall appears like holographic graffiti, and, beyond it, the image splits, the painting becomes an asymmetrical diptych: a bent arm, disappearing into sketchy lavender sheets, props up an unseen head.

Did I harm? Did I heal? Anthony Cudahy’s painting’s title asks.

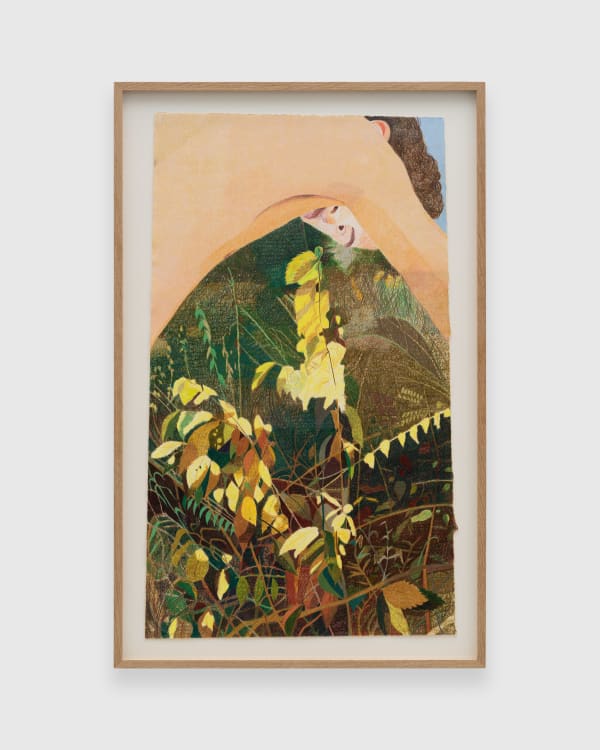

The scientist Nicolas Andry, who coined the term “orthopedia” in 1741, proposed a sapling bound to a board as the field’s symbol, like the one sprouting in The inability to know another (Paul and bound tree). He was trying to help children right themselves, and he chose his area of study’s first Greek root, ortho, he wrote, since it “signifies straight, free from deformity.” On the one hand: the desire to correct, to discipline (Foucault did put Andry’s drawing, unremarked upon, in his book), or to nurture, maybe. On the other: the desire—or need—to vanish, to recede from straightening ropes and demarcating lines, to become a wash of color, to open a door to nowhere known.

If a portrait gets closer to anything, it’s unknowing. To try to find and fix the meaning behind any gesture or gaze would be misguided. Human yet architectonic, the arching arm could suggest an affordance unseen, like a knob or dial, something to open or change. Or it might suggest a wish to give or take. A gesture traces the empty air of narrative it can’t quite tell—like a Guston-like kettle, beside a man gazing at his own reflection, anticipates but does not generate a sound.

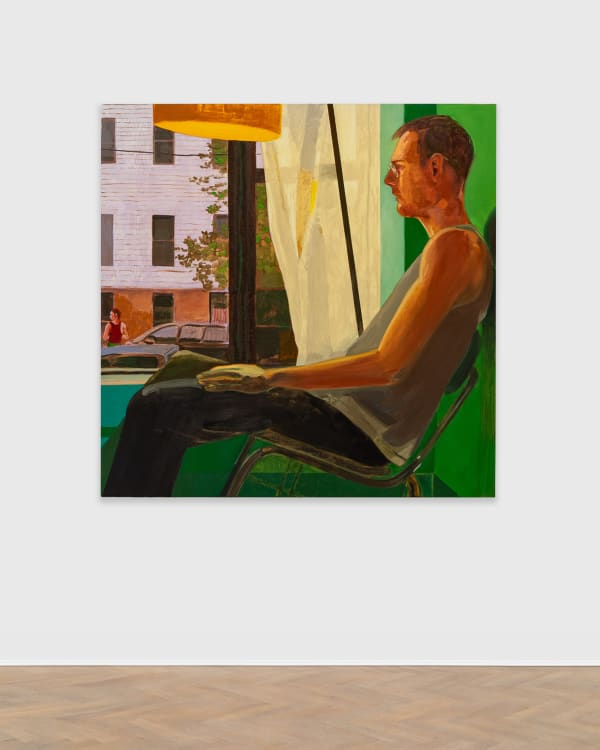

Borders dissolve, boundaries blur, a million portraits of a friend or lover only reveal more unknown wonders. Might this be true of the self, too? Painting the self in the studio in an implied Droste effect, the Solitary Arranger reaches toward the time when all will be just so—categorized and known, in its place.

The work is never done. As the saying goes: Idle hands…

The devil’s finger extends. His is one of the few hands shown in full. He’s an inky smudge. The Devil Points, indicating—or demanding?—that we should look, should see, should pay attention to something beyond the paper’s edge.

He floats upon a defined schema of arches and recessions which recall the spatial unreasoning of the altarpieces of Duccio or the tempera panels of Lorenzetti, who in the fourteenth century painted the active hands of Saint Nicholas, the active hands which raise the dead, toss coins, convince mariners to share their grains.

One story of Saint Nicholas tells of his felling a cypress. (Twisted? Gnarled? Salubriously erect? Who knows.) A demon inhabited this tree, and those who tried to cut it down had been killed. Nicholas exorcises the demon by slaying the tree with his bare hands. It would be ahistorical to call this a flipped version of an analogy common in medieval English poetry wherein foresters’ saws were depicted, what with their teeth, not only to gnaw but speak. Tools, to have value, it was thought, must be extensions of the body itself.

The Solitary Arranger might be reaching his brush to dip or dry it; again, the hand’s out of frame. The solitary arranger creates architectures which cast no shadows, flocks of birds, marriage quilts, floral visions of apocalyptic demise, and then, The Lovers (Triumph of Death): Each stepped part of a plane darkens to gold. Its selective third dimension luminesces a Sienese orangey rose. Bells and flames and abyss beyond. But, beside the guitar, its string broken in impossible angles, behind the book of looping patterns, the lovers sit. They are dressed. Their eyes meet, their wrists bend, interlace. Their hands are unseen but not off frame: they disappear into a crook of an elbow, an unbuttoned shirt. Time or body, landscape or image, pattern or person, present or past—loops and repetitions unstick. Pointing, reaching, grasping, arranging—hands move beyond boundaries or beyond the self to evoke a future as-of-yet decided or known, to create a connection, or merely to indicate something, or somewhere, else.

Written by Drew Zeiba, August 2025

About the artist

Anthony Cudahy (b. 1989, Ft. Myers, FL, US) received his MFA from Hunter College, New York, NY (US) in 2020.

Cudahy weaves imagery culled from photo archives, art history, film stills, hagiographic icons and personal photographs to explore themes of queer identity and tenderness. His evocative figurative paintings and drawings are informed by extensive historical research. They negotiate feelings of loneliness, isolation, desire, and safety through the lens of the artist’s own autobiographical narratives and crafted mythologies.

His solo exhibition Spinneret debuted at the Ogunquit Museum of American Art, ME (US), and travelled to the Green Family Art Foundation in Dallas, TX (US) in 2024, accompanied by a dedicated publication. Cudahy held his first solo museum exhibition in 2023, titled Conversation, at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dole in France. His work has also been included in numerous international group exhibitions.

His work can be found in collections of the AkzoNobel Art Foundation, Amsterdam (NL); Baltimore Museum of Art, MD (US); Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University, CA (US); Dallas Museum of Art, TX (US); The David and Indre Roberts Collection, London (UK); Fundación Medianoche0 (ES); Green Family Art Foundation, Dallas, TX (US); The Hort Family Collection, New York, NY (US); Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, FL (US); Kunstmuseum, The Hague (NL); Les Arts au Mur Artothèque de Pessac, Pessac (FR); Museum of Contemporary Art North Miami, FL (US); The New York Historical, New York, NY (US); Speed Art Museum, Louisville, KY (US); and Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam (NL).